· 9 min read

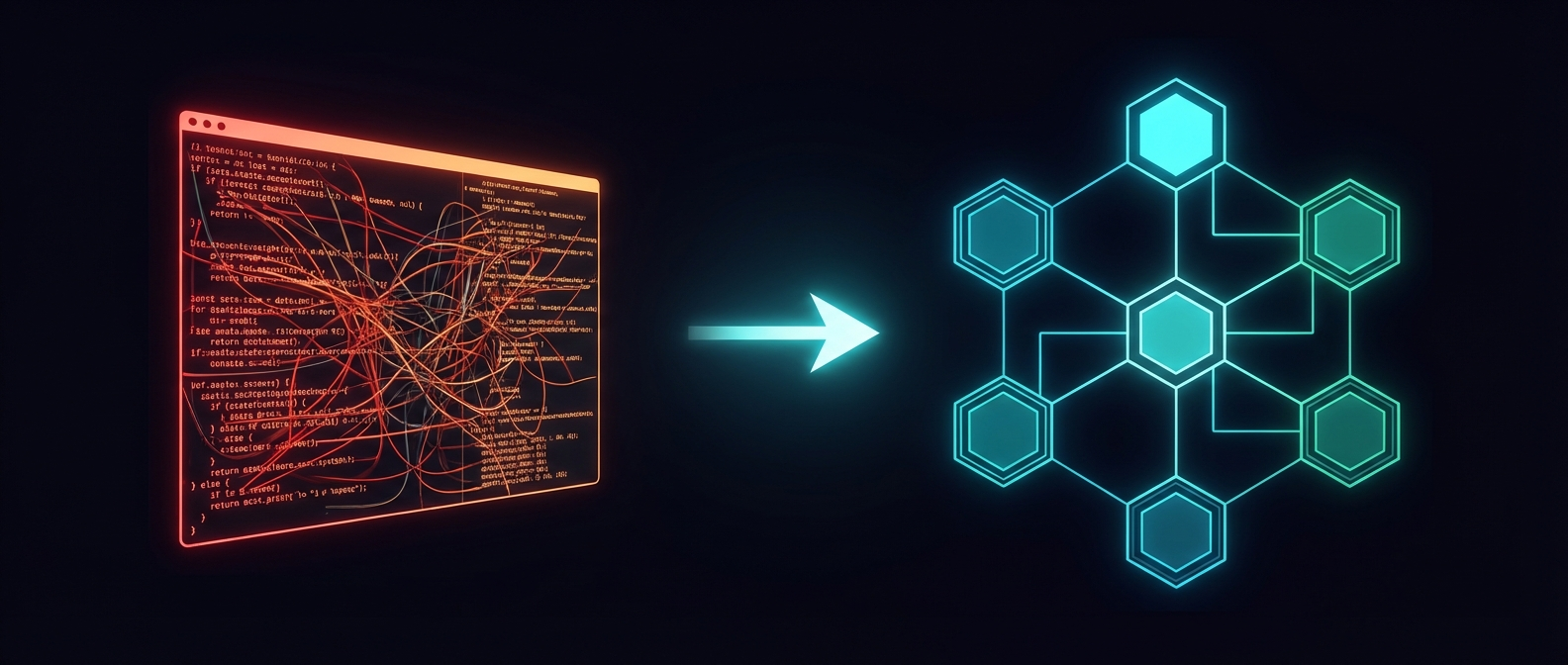

Listeners with several functions in Kotlin. How to make them shine?

One question I get often is how to simplify the interaction with listeners that have several functions on Kotlin. For listeners (or any interfaces) with a single function is simple: it automatically lets you replace it by a lambda. But that’s not the case for listeners with several functions.

So in this article I want to show you different ways to deal with the problem, and you may even learn some new Kotlin tricks on the way!

The problem

When we’re dealing with listeners, let’s say the OnclickListener for views, thanks to optimizations that Kotlin do over Java libraries, we can turn this:

view.setOnClickListener(object : View.OnClickListener {

override fun onClick(v: View?) {

toast("View clicked!")

}

})

into this:

view.setOnClickListener { toast("View clicked!") }

The problem is that when we get used to it, we want it everywhere. But this doesn’t escalate when the interface has several functions.

For instance, if we want to set a listener to a view animation, we end up with this “nice” code:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener(object : Animator.AnimatorListener {

override fun onAnimationStart(animation: Animator?) {

toast("Animation Start")

}

override fun onAnimationRepeat(animation: Animator?) {

toast("Animation Repeat")

}

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator?) {

toast("Animation End")

}

override fun onAnimationCancel(animation: Animator?) {

toast("Animation Cancel")

}

})

You may argue that the Android framework already gives a solution for it: the adapters. For almost any interface that has several methods, they provide an abstract class that implements all methods as empty. In the case above, you could have:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener(object : AnimatorListenerAdapter() {

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator?) {

toast("Animation End")

}

})

Ok, a little better, but this have a couple of issues:

- The adapters are classes, which means that if we want a class to act as an implementation of this adapter, it cannot extend anything else.

- We get back to the old school days, where we need an anonymous object and a function to represent something that it’s clearer with a lambda.

What options do we have?

Interfaces in Kotlin: they can contain code

Remember when we talked about interfaces in Kotlin? They can have code, and as such, you can declare adapters that can be implemented instead of extended (you can do the same with Java 8 and default methods in interfaces, in case you’re using it for Android now):

interface MyAnimatorListenerAdapter : Animator.AnimatorListener {

override fun onAnimationStart(animation: Animator) = Unit

override fun onAnimationRepeat(animation: Animator) = Unit

override fun onAnimationCancel(animation: Animator) = Unit

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator) = Unit

}

With this, all functions will do nothing by default, and this means that a class can implement this interface and only declare the ones it needs:

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity(), MyAnimatorListenerAdapter {

...

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator) {

toast("Animation End")

}

}

After that, you can just use it as the argument for the listener:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener(this)

This solution eliminates one of the problems I explained at the beginning, but it forces us to still declare explicit functions for it. Missing lambdas here?

Besides, though this may save from using inheritance from time to time, for most cases you’ll still be using the anonymous objects, which is exactly the same as using the framework adapters.

But hey! This is an interesting idea: if you need an adapter for listeners with several functions, better use interfaces rather than abstract classes. Composition over inheritance FTW.

Extension functions for common cases

Let’s move to cleaner solutions. It may happen (as in the case above) that most times you just need the same function, and not much interested in the other. For AnimatorListener, the most used one is usually onAnimationEnd. So why not creating an extension function covering just that case?

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.onAnimationEnd { toast("Animation End") }

That’s nice! The extension function is applied to ViewPropertyAnimator, which is what animate(), alpha, and all other animation functions return.

inline fun ViewPropertyAnimator.onAnimationEnd(crossinline continuation: (Animator) -> Unit) {

setListener(object : AnimatorListenerAdapter() {

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator) {

continuation(animation)

}

})

}

I’ve talked about

inlinebefore, but if you still have some doubts, I recommend you to take a look at the official reference.

As you see, the function just receives a lambda that is called when the animation ends. The extension does the nasty work for us: it creates the adapter and calls setListener.

That’s much better! We could create one extension function per function in the listener. But in this particular case, we have the problem that the animator only accepts one listener. So we can only use one at a time.

In any case, for the most repeating cases (like this one), it doesn’t hurt having a function like this. It’s the simpler solution, very easy to read and to understand.

Using named arguments and default values

But one of the reasons why you and I love Kotlin is that it has lots of amazing features to clean up our code! So you may imagine we still have some alternatives. Next one would be to make use of named arguments: this lets us define lambdas and explicitly say what they are being used for, which will highly improve readability.

We can have a function similar to the one above, but covering all the cases:

inline fun ViewPropertyAnimator.setListener(

crossinline animationStart: (Animator) -> Unit,

crossinline animationRepeat: (Animator) -> Unit,

crossinline animationCancel: (Animator) -> Unit,

crossinline animationEnd: (Animator) -> Unit) {

setListener(object : AnimatorListenerAdapter() {

override fun onAnimationStart(animation: Animator) {

animationStart(animation)

}

override fun onAnimationRepeat(animation: Animator) {

animationRepeat(animation)

}

override fun onAnimationCancel(animation: Animator) {

animationCancel(animation)

}

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator) {

animationEnd(animation)

}

})

}

The function itself is not very nice, but that will usually be the case with extension functions. They’re hiding the dirty parts of the framework, so someone has to do the hard work. Now you can use it like this:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener(

animationStart = { toast("Animation start") },

animationRepeat = { toast("Animation repeat") },

animationCancel = { toast("Animation cancel") },

animationEnd = { toast("Animation end") }

)

Thanks to the named arguments, it’s clear what’s happening here.

You will need to make sure that nobody uses this without named arguments, otherwise it becomes a little mess:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener(

{ toast("Animation start") },

{ toast("Animation repeat") },

{ toast("Animation cancel") },

{ toast("Animation end") }

)

Anyway, this solution still forces us to implement all functions. But it’s easy to solve: just use default values for the arguments. Empty lambdas will make it:

inline fun ViewPropertyAnimator.setListener(

crossinline animationStart: (Animator) -> Unit = {},

crossinline animationRepeat: (Animator) -> Unit = {},

crossinline animationCancel: (Animator) -> Unit = {},

crossinline animationEnd: (Animator) -> Unit = {}) {

...

}

And now you can do:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener(

animationEnd = { toast("Animation end") }

)

Not bad, right? A little more complex than the previous option, but much more flexible.

The killer option: DSLs

So far, I’ve been explaining simple solutions, which honestly may cover most cases. But if you want to go crazy, you can even create a small DSL that makes things even more explicit.

The idea, which is taken from how Anko implements some listeners, is to create a helper which implements a set of functions that receive a lambda. This lambda will be called in the corresponding implementation of the interface. I want to show you the result first, and then explain the code that makes it real:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener {

onAnimationStart {

toast("Animation start")

}

onAnimationEnd {

toast("Animation End")

}

}

See? This is using a small DSL to define animation listeners, and we just call the functions that we need. For simple behaviours, those functions can be one-liners:

view.animate()

.alpha(0f)

.setListener {

onAnimationStart { toast("Start") }

onAnimationEnd { toast("End") }

}

This has two pros over the previous solution:

- It’s a little cleaner: you save some characters here, though honestly not worth the effort only because of that

- It’s more explicit: it forces the developer say which action they’re overriding. In the previous option, it was up to the developer to set the named argument. Here there’s no option but to call the function.

So it’s essentially a less-prone-to-error solution.

Now to the implementation. First, you still need an extension function:

fun ViewPropertyAnimator.setListener(init: AnimListenerHelper.() -> Unit) {

val listener = AnimListenerHelper()

listener.init()

this.setListener(listener)

}

This function just gets a lambda with receiver applied to a new class called AnimListenerHelper. It creates an instance of this class, makes it call the lambda, and sets the instance as the listener, as it’s implementing the corresponding interface. Let’s see how AnimeListenerHelper is implemented:

class AnimListenerHelper : Animator.AnimatorListener {

...

}

Then, for each function, it needs:

- A property that saves the lambda

- The function for the DSL, that receives the lambda executed when the function of the original interface is called

- The overriden function from the original interface

private var animationStart: AnimListener? = null

fun onAnimationStart(onAnimationStart: AnimListener) {

animationStart = onAnimationStart

}

override fun onAnimationStart(animation: Animator) {

animationStart?.invoke(animation)

}

Here I’m using a type alias for AnimListener:

private typealias AnimListener = (Animator) -> Unit

This would be the complete code:

fun ViewPropertyAnimator.setListener(init: AnimListenerHelper.() -> Unit) {

val listener = AnimListenerHelper()

listener.init()

this.setListener(listener)

}

private typealias AnimListener = (Animator) -> Unit

class AnimListenerHelper : Animator.AnimatorListener {

private var animationStart: AnimListener? = null

fun onAnimationStart(onAnimationStart: AnimListener) {

animationStart = onAnimationStart

}

override fun onAnimationStart(animation: Animator) {

animationStart?.invoke(animation)

}

private var animationRepeat: AnimListener? = null

fun onAnimationRepeat(onAnimationRepeat: AnimListener) {

animationRepeat = onAnimationRepeat

}

override fun onAnimationRepeat(animation: Animator) {

animationRepeat?.invoke(animation)

}

private var animationCancel: AnimListener? = null

fun onAnimationCancel(onAnimationCancel: AnimListener) {

animationCancel = onAnimationCancel

}

override fun onAnimationCancel(animation: Animator) {

animationCancel?.invoke(animation)

}

private var animationEnd: AnimListener? = null

fun onAnimationEnd(onAnimationEnd: AnimListener) {

animationEnd = onAnimationEnd

}

override fun onAnimationEnd(animation: Animator) {

animationEnd?.invoke(animation)

}

}

The resulting code looks great, but at the cost of doing much more work.

What solution should I use?

As usual, it depends. If you’re not using it very often in your code, I would say that none of them. Be pragmatic in these situations, if you’re going to write a listener once, just use an anonymous object that implements the interface and keep writing code that matters.

If you see that you need it more times, do a refactor with one of these solutions. I would usually go for the simple extension that just uses the function we are interested in that moment. If you need more than one, then evaluate which one of the two latest alternatives works better for you. As usual, it depends on how extensively you’re going to use it.

Hope this lines help you next time you find yourself in a situation like this. If you solve this differently, please let me know in the comments!

Thanks for reading 🙂